We do it all for guys like this.

A while ago I mentioned a new bridge going in on one of my favorite routes across the tidal flatlands south of where I live.

The purpose of the bridge was to allow a new channel to be created where the highway blocked tidal flows from flushing through the marsh.

In the olden days, water flowed in and out; more than 100 years ago, some folks blocked off the outlet to the ocean so they could hunt ducks in the lagoon; later on, the highway went in across the same artificial sandspit, and an electric railway too.

The electric railway stopped running when they made "Who Framed Roger Rabbit." The highway remains, and is used by thousands of cars every day, probably tens of thousands.

Also by many bicyclists.

The purpose of the bridge was to allow a new channel to be created where the highway blocked tidal flows from flushing through the marsh.

In the olden days, water flowed in and out; more than 100 years ago, some folks blocked off the outlet to the ocean so they could hunt ducks in the lagoon; later on, the highway went in across the same artificial sandspit, and an electric railway too.

The electric railway stopped running when they made "Who Framed Roger Rabbit." The highway remains, and is used by thousands of cars every day, probably tens of thousands.

Also by many bicyclists.

This week they tore down the berm separating the new inlet from the sea, and for the first time in over 100 years, the marooned lagoon can breathe free.

The earthmovers broke the berm around 4 a.m., at low tide. They said it would take about six hours (the span of a rising tide) for the ocean to flood in and fill the marsh.

The earthmovers broke the berm around 4 a.m., at low tide. They said it would take about six hours (the span of a rising tide) for the ocean to flood in and fill the marsh.

The new bridge has a gracious design, including little viewing platforms where cyclists and pedestrians can stand out of the flow of traffic and have a look at the water flowing underneath.

The last step required before letting the water through into the inner lagoon was the construction of a second bridge for utility traffic to and from a series of oil wells that sit near the entrance to Bolsa Bay. This bridge was finished a month or so ago, and water now flows underneath it too on its way into the estuary.

After all that work to open the waterway, it was gratifying to see native species clambering over the rocks almost right away, reclaiming the territory they had been denied for years.

As of this week, the tide (which was quite strong flowing through this channel) was still stirring up a lot of turbulation from loose sand and silt in the water. I imagine that will persist until the new channel bottom stabilizes a little, and native seaweeds take hold to help clump things together. (This picture exaggerates the visibility of the clouds in the water.)

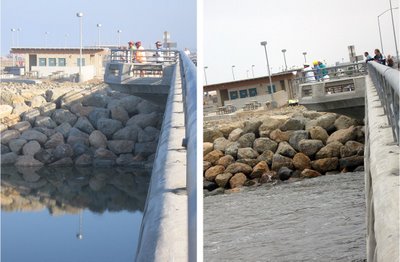

Before . . .

. . . after.

After all that work to open the waterway, it was gratifying to see native species clambering over the rocks almost right away, reclaiming the territory they had been denied for years.

As of this week, the tide (which was quite strong flowing through this channel) was still stirring up a lot of turbulation from loose sand and silt in the water. I imagine that will persist until the new channel bottom stabilizes a little, and native seaweeds take hold to help clump things together. (This picture exaggerates the visibility of the clouds in the water.)

Before . . .

. . . after.